Fall 2025 Capstone Paper

The Last Best Place: Problems and Solutions at the Wildland Urban Farmland Interface

Foreword By Beowulf Boswell and Patrick Lingle:

The Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem (GYE) contains over 22 million acres of land, providing crucial habitat for elk herds, grizzly bears, wolves, cutthroat trout, and numerous other species. For more than 11,000 years, humans have inhabited the GYE alongside these wildlife species (NPS 2025b). From early native tribes to modern day cities such as Bozeman, the GYE has seen a large increase in urbanization. In recent years, Bozeman’s population has increased from 37,000 in 2010 to nearly 60,000 in 2025 (World Population Review 2025). With this rapid growth, issues such as habitat loss and habitat fragmentation have become a threat to wildlife across the GYE. Rapid urbanization leads to decreased biodiversity and habitat degradation (Chen et al. 2025). Grassland birds are an excellent example of the impacts of urbanization.

Habitat fragmentation in the GYE is not limited to the construction of apartment buildings or single-family homes, as changes in land use and cover also impact habitat. As cities expand, the number of structures vulnerable to fire also increases. As a consequence of this increase, more effort and more chemicals are being used to suppress wildfires in the wildland urban interface (WUI). In addition to the physical destruction of buildings, excess nutrients and harmful PFAS chemicals are introduced to the soil. These additions can contaminate water supplies and alter plant growth.

Lastly, transportation corridors and human barriers can also impact habitat, migration routes, and mortality rates (Malcom 2018). Major highways like Interstate 90 and US Highway 191 also act as a physical barrier for migration. In addition to highways, other physical barriers such as fences can make accessibility more difficult for migratory wildlife. These barriers can block off crucial habitat or routes to habitat, especially for elk populations within the GYE. Physical barriers are not limited to road barriers, river structures like dams and reservoirs can also impact salmon and trout migration routes and habitat. Understanding how to mitigate these new issues is critical in preserving local wildlife populations and migration routes. If these issues are not addressed, habitat areas will continue to decrease.

Agricultural systems have a large impact on habitat. The physical alteration of the landscape as well as possible water contamination from fertilizers and pesticides impact both fish and wildlife habitats (Skoog et al. 2024). Cutthroat trout are one of many species impacted by the increased sediment load from tilling.

Agricultural lands are a recent part of the equation for managing the wildland-urban

interface. As water availability becomes less predictable, producers across the West

face growing pressure to adapt to a shifting climate. Many dryland grain farmers are

shifting from traditional fallow rotations to continuous or cover cropping systems

that increase soil organic 2 matter, enhance water infiltration, and stabilize yields

under dry conditions. However, rising

temperatures and increasingly erratic precipitation patterns have added an additional

layer of uncertainty, forcing producers to adjust planting schedules and adopt water-efficient

management strategies to maintain soil health and yield stability. These same climate

pressures make building soil resilience more important than ever.

Compost use has become one of the most effective ways to strengthen that resilience, restoring soil structure, boosting water-holding capacity, and supporting the microbial activity that sustains fertility over time. Composting is consistent with regenerative agricultural practices that prioritize soil health, animals, and people for treating the farm as an interconnected ecosystem and reducing the environmental harms of industrial agriculture. Together, these strategies illustrate how agricultural innovation can buffer farms against drought and degradation while reducing dependence on synthetic inputs.

Organic and regenerative agriculture emphasize the importance of minimizing the use of chemicals. Heavy use of glyphosate, the world’s most common herbicide, leaves residues that harm crops and native plants while diminishing soil microbial diversity. The same is true for overused insecticides, which can wash into streams. A more sustainable approach relies on parasitoid wasps and other biological controls that limit pests without damaging ecosystems.

In addition to agricultural chemicals, water in the state can be contaminated from natural sources. In Montana, groundwater can harbor arsenic, uranium, and bacteria including Mycobacteria and Legionella, creating significant health risks for private well users. While treatment systems are available, they are expensive and challenging to maintain. Meanwhile, PFAS, so-called “forever chemicals” originating from firefighting foam and industrial runoff, represent a new class of persistent pollutants. These compounds accumulate in sediment and food webs, persisting for decades. Recent studies indicate that biochar filtration may provide an affordable and sustainable method for eliminating such contaminants. Despite these efforts, engineered fixes have consequences: dams trap sediment, slow water flow, and create low-oxygen zones that turn chemicals into their most toxic forms. This illustrates that even carefully designed solutions can introduce new challenges, highlighting the need for cautious and informed approaches.

The Gallatin Valley, part of the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, shows how development, agriculture, and climate pressures converge around water. Once dominated by farmland and open range, it has become one of Montana’s fastest-growing regions, with Bozeman’s population nearly doubling in just over a decade. That population growth, layered over a long history of cropland and hayfield irrigation, has pushed both surface and groundwater systems to their limits. The same rivers that shaped the valley’s economy now reflect the cumulative effects of diversion, groundwater pumping, and warming temperatures.

Long-term U.S. Geological Survey records from Hyalite Creek and the Gallatin River

confirm a clear, basin-wide decline in streamflow since the 1970s (Table 1). However,

the magnitude and drivers of this decline vary across the valley. In the upper basin,

Hyalite Creek shows a relatively modest reduction in flow that aligns with climatic

trends—earlier snowmelt, reduced snowpack, and shifting runoff timing. Because Hyalite

receives minimal direct

withdrawals and has limited anthropogenic alteration, its decline reflects the broader

climatic pressures acting on headwater systems across the northern Rockies. However,

these small reductions matter, as they shorten the late-summer baseflow period.

In contrast, mid- and lower-basin sites show steeper declines linked to the valley’s growing water use. The Gallatin River near Gateway experiences the sharpest drop in discharge because it is at the center of agricultural diversions, groundwater pumping, and delayed irrigation return flows. Unlike headwater streams, this location receives almost no additional inflow from side tributaries, meaning every gallon removed for irrigation in the Gallatin Canyon directly reduces discharge. Downstream near Three Forks, the cumulative effect becomes clear: even with some return flow re-entering the system, the total amount of water leaving the valley is decreasing, indicating that withdrawals, and shifting hydrologic timing now exceed natural replenishment. The rest of the valley is declining faster than Hyalite, with human use, not climate alone, driving the majority of the observed reductions.

Regional research across the Interior West shows that declining streamflows are occurring

throughout snowmelt-fed river systems. More than 200 monitored watersheds across the

Colorado, Columbia, and Missouri River basins exhibit 10–20% reductions in late-season

discharge as irrigation intensifies and meltwater arrives earlier in the year (Ketchum,

2023). Statewide analyses show similar patterns, with long-term declines in peak flows

across Montana and northern Wyoming accompanied by shifts in runoff timing driven

by warming temperatures

and reduced snowpack (Sando, 2025). These regional trends mirror the underlying processes

shaping conditions in the Gallatin Valley, where altered flow timing and reduced discharge

interact with expanding surface-water pathways to drive warmer, slower late-summer

streams.

Yet declining discharge is only part of the hydrologic shift occurring in the Gallatin Valley. As more water is routed through an expanding network of irrigation ditches, subdivisions, and channels, the total surface area of flowing water across the landscape has increased dramatically. This redistribution exposes water to more solar radiation, warmer air temperatures, and longer residence times, allowing it to heat up before re-entering natural streams. This warmer return flow combines with reduced main-stem discharge to create shallower, slower, and hotter late-summer conditions. This transition directly sets the stage for ecological stress downstream.

These numbers point to more than just hydrological change; they reveal a system reaching

its physical and legal limits. The valley’s groundwater aquifer is over-allocated,

and each new domestic well further reduces stream baseflow. Under Montana’s “use it

or lose it” water rights framework, senior right holders must continue diverting their

full allotments each season or risk forfeiting them, leaving little incentive to conserve.

This combination of growth, policy, and natural decline creates a feedback loop where

even modest reductions in snowpack or

runoff cascade into larger ecological and economic impacts. Warmer streams hold less

oxygen, forcing species like westslope cutthroat trout into shrinking cold-water refuges,

while lower flows reduce dilution of nutrients and contaminants, worsening water quality.

Despite these challenges, local adaptation is underway. Some new developments and agricultural operations are experimenting with greywater reuse, low-energy filtration, and nanomaterial treatment systems to offset summer demand. Riparian restoration projects are also reconnecting floodplains and stabilizing banks, while compact urban planning seeks to reduce the hydrological footprint of growth. Yet, evidence indicates that surface-level interventions alone are insufficient: lasting sustainability depends on the integration of groundwater monitoring, return-flow accounting, and conservation incentives that reconcile human and ecological water demands.

Bozeman and the Gallatin Valley offer a clear picture of the modern West: a landscape where population growth, water scarcity, and innovation all intersect. The trends in streamflow are not just indicators of loss, but warnings of imbalance. Opportunities to rethink how water is shared, measured, and valued in a rapidly changing environment.

Natural cycles in the West are now operating within a new set of human and climatic

constraints. Snowmelt, fire, and flood events still happen, but their timing and strength

are increasingly shaped by warming temperatures, development, and the infrastructure

built across these landscapes. Dams, diversions, roads, and other human altered land

cover shift how water, nutrients, and wildlife move through an ecosystem. As these

pressures build, the effects become clear in wildlife, whose daily movements and seasonal

patterns reveal how much these

ecosystems are being reshaped.

Wildlife

Introduction

The GYE and surrounding Montana landscapes face mounting pressures from human development that threaten native wildlife across multiple ecosystems. As Montana's population has grown and urbanization has intensified, native species are forced to adapt to dramatically altered environments or face extirpation (National Park Service, 2024). Habitat destruction and fragmentation caused by highways, fencing, and urban expansion have disrupted essential ecological processes that wildlife depend upon for survival. For centuries, Rocky Mountain elk have traversed the wilderness expanse of the GYE, embarking on long-distance migrations from mountainous summer ranges to lower elevation winter ranges each year. However, human-dictated landscape fragmentation has reduced the connectivity of these migration corridors, forcing elk to navigate an increasingly obstacle-laden environment. Similarly, native birds face parallel challenges from climate change, competition with non-native species, and especially habitat destruction. Beyond terrestrial ecosystems, Montana's aquatic environments face distinct but equally pressing threats stemming from the diversion of substantial volumes from the Gallatin Valley's rivers and streams during critical growing months, proving particularly harmful to species like the westslope cutthroat trout, which relies on cold, navigable waters with ample dissolved oxygen levels throughout its life cycle (USGS, 2025). Together, these interconnected pressures from habitat destruction, landscape fragmentation, and water management practices illustrate the broad-scale and multifaceted impacts of human development on Montana's diverse ecosystems.

This section focuses on the effects of human development on three different animals in Montana’s ecosystems. The species of interest are elk, native birds, and westslope cutthroat trout.

Habitat Fragmentation Effects on Elk By Maxwell Opton

Every year, elk herds embark on long-distance migrations from mountainous summer ranges to lower elevation winter ranges. These migrations are essential for accessing seasonal forage and reproductive success within the herd. On a larger scale, elk transport nutrients across elevation gradients, help to shape plant communities, and influence predator dynamics (Sawyer et al., 2013). However, human development has been expanding and intensifying in this region, disrupting these migrations. Within the GYE, housing density has tripled in the last 50 years (National Park Service, 2024). Human-dictated habitat fragmentation caused by highways, fencing, and overall urban expansion has reduced the connectivity of this landscape.

Yellowstone elk historically spent their winters in the foothills and plains before

climbing into the mountains for summer (Skinner, 1925). Elk are grazing animals that

eat primarily grasses, which dictates the land they occupy and migrate to. Elk initiate

movement to lower-elevation winter ranges as soon as snowfall begins to accumulate,

and forage accessibility becomes limited (Smith et al., 2019). The problem is that

the lower elevations of winter forage

lands are now occupied by ranches and crisscrossing fences. Estimates suggest that

there are over 150,000 miles of fencing within the winter range habitat for elk in

the GYE (Kudelska, 2025). Elk can get tangled in fencing or injured trying to jump

over them, which increases mortality. These fences are a direct cause of habitat fragmentation,

representing a barrier that elk have to migrate around to reach their ranges. Habitat

fragmentation occurs when a once-continuous habitat is broken into smaller, disconnected

patches that are separated by areas

of varying habitat type (Wilcove et al. 1986). Anthropogenically, this can be caused

by development in forms of roads, trails, fences, and infrastructure. We’re changing

the habitat in a way that suits us, which can then have more widespread effects. The

larger impacts from this include reduced species diversity, increased forms of pollution,

as well as the spread of invasives (Millhouser, 2019).

Roads and highways are not only crossing hazards for elk, but they’re large-scale agents of fragmentation that reshape the ecology and management of migratory herds. Displacement effects of highways can extend up to 1.1 miles from the roadway, effectively creating a wide corridor of reduced habitat utility (Ruediger et al., 2005). When highways like 14 or 212 slice through migration routes, the loss of usable habitat includes broad swaths of adjacent winter and migration habitat. This displacement both fragments of seasonal ranges and compresses elk into fewer areas of refuge. Elk may also expend more energy to avoid roads, reducing foraging efficiency, and reproductive success.

The primary way of solving this is to create large, well-designed corridors through overpasses or tunnels accompanied by strategic fencing. These crossings need to be large, sited correctly, and paired with fencing that funnels the animals to the structure (Ruediger et al., 2005). While the crossings don’t restore the adjacent habitat lost from highways, they allow migratory species to navigate human-modified terrain.

Habitat fragmentation in the GYE has disrupted the natural migrations of elk by breaking

up continuous landscapes with roads, fencing, and development. These barriers force

herds to alter routes, avoid high-traffic areas, and rely more on private lands, leading

to increased mortality risks, disease transmission, and reduced access to forage.

These changes extend across the Western U.S., reflecting a broader regional pattern

of habitat connectivity loss and diminished ecosystem resilience. To protect migratory

elk and the ecological functions they

sustain, management must focus on maintaining and restoring landscape connectivity.

Conservation strategies such as wildlife crossings, zoning regulations, and partnerships

with private landowners are essential for ensuring elk can continue to move freely

between seasonal ranges. Protecting these migrations will not only sustain elk populations

but also help preserve the ecological balance of the GYE.

Native Birds Impacts By Brooks Taylor:

With so many people moving to Montana, native birds face obstacles including climate change, competition with non-native species, and especially habitat destruction. As Montana has become more urbanized, birds need to adapt to urban environments or face extirpation. Habitat destruction has severely affected native birds not only in Montana, but also throughout the entire US. Loss of habitat puts birds in situations where they are forced to deal with anthropogenic stressors. As a result, nearly 1 billion birds die each year from humans (Loss, 2015). Some of the birds that have been directly threatened by habitat destruction in the GYE include the western meadowlark and loggerhead shrike. This is especially true for grassland birds due to reliance on grasslands for their shelter and foraging.

Grassland’s conversion to urban areas remains one of the largest threats to biodiversity in North America, and this directly affects grassland birds. A major threat is a lack of grassland protection. Only 4% of the grasslands in the world are protected (Peterman, 2021). Grasslands are important due to the various ecosystem services and functions they provide. Functions and services of grasslands provide food through hunting, nourishment for the soul from being in nature, and important habitat for animals such as birds, squirrels and coyotes. As grasslands are turned into urban areas, the prairie ecosystem and its benefits are destroyed. Habitat destruction has negatively impacted grassland birds because of native grassland conversion to farmlands, severely affecting grassland bird species.

A species especially affected by loss of grasslands is the western meadowlark. Western meadowlarks rely on grasslands for nesting and cover from predators (Giovanni, 2015). They primarily prefer native grasslands and are less abundant in the grasslands of introduced species. The western meadowlark, a yellow, white, and brown passerine bird, lives in native, tall agricultural grasslands, roadsides, pastures, and orchards (MTNHP, 2025). Though their numbers are stable in Montana, they are declining at a rate of about 1% per year and have lost 47% of their population since 1970 (Mackin, 2024).

Unlike the western meadowlark whose population is stable, the Sprague’s pipit is under considerably more threat by habitat destruction. This small grassland bird occupies the grasslands of southern Canada and the northern great plains. Their range includes the states and provinces of Alberta, southwestern Manitoba, Saskatchewan, central and eastern Montana, central North Dakota, and northwestern South Dakota (Staufer, 2025). This white and dark brown bird, like western meadowlark, lives primarily on the ground and feeds insects. Currently, they’re in dire straits, losing roughly 4% of their habitat per year for a loss of 50% of their habitat since 1975 (Cornell, 2025). As a habitat specialist that only lives in native grasslands, the Sprague’s pipit is unable to live in conventional farm systems.

Though more abundant than Sprague’s pipit, loggerhead shrikes are also in rapid decline. Loggerheads are generalists who can live in a variety of habitats such as prairies, agricultural fields, low trees, golf courses, and pastures with fences (Cornell, 2025). In Montana, they are found throughout the entire state but are listed as a species of concern (Cornell, 2025). They possess many characteristics of raptors such as a sharpened beak and talons, but they are much smaller than most other birds of prey. The use of thorns and barbed wire to impale their prey. Despite their adaptability to different environments, they require open spaces to capture prey which can include rabbits and lizards. As of now, they’ve lost 75% of their population since 1966 and lose about 2.5% of their habitat per year.

Grasslands and the birds living in them are in peril, but what is being done to protect these areas? One effort currently is the North American Grasslands Conservation Act. This act gives 60 million dollars in grants to support conservation efforts in the US and in Montana (United States Congress, 2024). This bill is funding restoration to grasslands falling under the criteria that are threatened by crop conversion and woody encroachment (United States Congress, 2024). Additionally, the Perry Sodbuster Act of 1985 is meant to prevent farmers from cultivating land that has high erosion potential (Rollins, 2020). If land has one-third of its acreage affected by eroded soil, then the entirety of the land can’t be cultivated. This means land that isn’t prone to erosion and full of native vegetation can be converted to cropland. Grassland that is grazed to the bottom few inches of the soil destroy bird habitat and gives weeds a prime opportunity to invade the soil. There is no definitive evidence showing these bird species decline solely because of habitat fragmentation as very few studies have been conducted. The only way to study whether habitat fragmentation contributes to decline is doing a controlled experiment were a group of grassland birds live in a prairie, the prairie is converted into an urbanized area or farmland, and the response of the birds to the fragmentation is recorded.

Habitat destruction is the biggest driver in biodiversity loss, and it’s apparent that many of the birds we know and love in Montana are at risk of losing all their habitat, and this is especially true of grassland birds. All three of these birds; the loggerhead shrike, western meadowlark, and Sprague’s pipit are rapidly declining as their habitat is developed and farmed. Grasslands are declining at rapid rates as the need for urban development is valued more than sustainability of our ecosystems. Western meadowlarks have lost nearly 47% of their habitat since 1950 and are losing 1% of their habitat per year. Loggerhead shrikes and Sprague’s pipits are also losing their habitat at 1-5% per year as they slowly start to head towards possible extirpation. Habitat destruction is one of many obstacles grassland birds face that puts them in jeopardy of losing their effect on ecosystems such as vectors of seed dispersal and prey for other animals.

Westslope Cutthroat Trout Ecosystem Impacts By Samuel Gabrielson

A significant element of Montana water law is the application of the “use it or lose

it” principle. Since most water sources are over-appropriated in Montana, those who

hold water rights must put the water to beneficial use to be protected from challenges

of abandonment. Abandonment of a water right includes losing the right to the next

most senior right holder (DNRC, n.d.). This structure creates an incentive for rights

holders to use their full allocation every year, even during typically wetter periods

when conservation of the water could be beneficial, for fear of abandonment of their

right. This incentive is harmful to certain ecological communities, such as that of

the westslope cutthroat trout. The westslope cutthroat trout relies on cold, navigable

waters with ample dissolved oxygen levels for their life cycle, which will be addressed

in this study (USGS, 2025).

This framework of water allocation is visible throughout the Gallatin Valley in the

form of diversion structures, ditch systems, and holding ponds. These structures represent

centuries of investment in water capture and movement and can range in size from small

headgates on creeks to elaborate systems on larger rivers, such as dams and levees.

This infrastructure, built over the last couple hundred years, has created a highly

engineered and altered landscape in which the vast majority of surface water during

irrigation season is legally claimed (MSU Extension,

2025).

Irrigation intensification, land-use change, and groundwater development have collectively

altered hydrological conditions across the northern Rocky Mountains. Negative summer

flow responses have been documented across more than 200 basins in the Colorado River,

Columbia River, and Missouri River systems, with return flows lagging by several months

and proving insufficient to offset summer water losses (Ketchum, et al., 2023). A

typical natural

flow regime in Montana features high spring runoff driven by snowmelt, declining flows

through summer as the snowpack depletes, and stable baseflows during fall and winter

maintained by groundwater contributions (USGS, 2025). The decline observed at the

Gallatin River near Three Forks reflects this pattern, suggesting that irrigation

withdrawals and delayed return flows reduce available discharge in streams during

the critical July–September low-flow period. These regional findings align with patterns

observed in the Gallatin Valley and indicate that declining

streamflows are driven by both climatic variability and intensified land and water

use (Sando, et al., 2025).

The Gallatin Valley’s aquifer system is now considered over-allocated. Thousands of

domestic and subdivision wells draw from shallow groundwater sources that are hydraulically

connected to surface water. Due to the Gallatin Valley’s unique geology, the aquifer

is segmented, which prevents continuous flow throughout (Rose and Waren, 2022). This

reduced linkage means that each new well can incrementally reduce stream baseflow,

complicating the

enforcement of senior surface-water rights and creating a legal quagmire within Montana’s

prior-appropriation framework. Continued subdivision development, conversion of rangeland

to residential properties, and fragmentation of riparian corridors have likely reduced

aquifer recharge and further exacerbated summer low-flow conditions throughout the

basin.

The Gallatin Valley data are consistent with regional studies of hydrological change. The observed trends support a narrative of converging climatic and anthropogenic pressures driving reductions in late-summer streamflow. In the upper valley, Hyalite Creek exemplifies the sensitivity of headwater systems to minor changes in baseflow. Mid-basin reaches, such as the Gallatin River near Gateway, highlight the cumulative effects of irrigation and municipal growth in areas of concentrated demand. The Gallatin River near Three Forks provides an integrated downstream perspective, where cumulative withdrawals and climatic changes manifest as reduced discharge at the basin outlet. The coherence of these findings with broader regional analyses suggests that hydrological change in the Gallatin Valley is both locally significant and reflective of larger-scale processes across the northern Rocky Mountains (Bell, et al., 2021).

Although this water is allocated by right, the persistence of agriculture and urban

expansion in the Gallatin Valley has created unique pressure on these surface water

systems. This convergence of municipal and agricultural demands has made water management

in the Gallatin Valley a complex act of balancing established water rights, supporting

economic growth, and protecting the hydrological integrity of natural systems which

is increasingly unable to stand against the rising competition. Removal of water for

irrigation or municipal use, while natural

flows are receding, only exacerbates the stress on aquatic ecosystems (USGS, 2025).

Headwater sites, though characterized by smaller absolute declines, are not exempt from this ecological risk. Even modest flow reductions can produce disproportionate habitat losses in high-gradient, coarse-bed channels typical of mountain headwaters; Hyalite Creek falls within this category (Ma, et al., 2023). Although, as reported, the recorded decline is only about 2 cfs per decade, such reductions during warm, low-flow periods can decrease velocity and depth in critical habitats, constraining ecological integrity and inducing ecological stress (Johnson, et al., 2024).

Disruption of these components in natural ecosystems due to surface water diversion causes a cascading effect through the food web. The Gallatin Valley suffers from a disrupted natural flow regime, which during the summer months (low-flow periods) causes warmer temperatures to persist in the river. Higher temperatures cause westslope cutthroat trout populations to decline, as they rely on cool waters for the increased dissolved oxygen it holds. This is not the only issue westslope cutthroat trout face due to low flow; loss of critical habitat, reduced spawning and rearing areas, and increased vulnerability to predation and disease are all increasingly common challenges (Earthzine, 2016). This limits fish from accessing their traditional spawning tributaries or eliminating tributaries all together. These issues also increase the risk of invasive species. Native fish, like the westslope cutthroat trout, are currently losing their habitat to the invasive rainbow trout. The mountain streams that westslope cutthroat trout prefer were historically too cold for rainbow trout but rising water temperatures have allowed rainbow trout to expand into cutthroat territory. This has led to westslope cutthroat and rainbow trout mating, reducing the number of genetically pure westslope cutthroats (USGS, 2025).

To mitigate the effects of surface water usage on stream ecosystems, the conservation

programs for the Gallatin River have focused on a wide range of initiatives. Current

and ongoing projects include improving riparian integrity, floodplain connectivity,

and improving spawning habitat (Gallatin River Drainage Physical Description, 2020).

Many of these projects are symptom focused, however, instead of mitigation focused.

For example, the inclusion of

groundwater analysis would deepen the understanding of declining surface flows. Irrigation

and residential development increasingly draw from groundwater sources, so aquifer

depletion may be masking or accelerating streamflow reductions. Systematic monitoring

of well levels would help clarify this dynamic and provide a more complete understanding

of the valley’s water budget. Future management will require coordinated strategies

that address both surface and groundwater. Conservation incentives, instream flow

protections, and adaptive allocation policies remain central, but these should be

paired with monitoring programs that link aquifer conditions to streamflow trends.

Protecting headwater baseflows, reducing peak-season withdrawals in mid-basin reaches,

and safeguarding cumulative flows at the basin outlet are all essential for maintaining

hydrological stability. While being beneficial for restoring habitat and helping facilitate

healthy waterways, current initiatives do not address the fundamental drivers of stream

dewatering. Without addressing the usage patterns, the current long-term trends suggest

that this ecosystem will continue to degrade (Gallatin River Drainage Physical Description,

2020).

Streamflows in the Gallatin Valley have declined significantly over the past 30–50 years, with reductions evident at Hyalite Creek, Gallatin River near Gateway, and Gallatin River near Three Forks. These declines reflect the cumulative effects of Montana’s water rights framework, irrigation intensification, rapid urban growth, and regional climatic shifts. These trends demonstrate the challenge of balancing agricultural production, municipal expansion, and ecological health in a constrained hydrological system.

In conclusion, the effects of surface water reductions have been indicated by reduced flow in each of the three sampled sites. From this, ecosystem effects of surface water reduction on the prized westslope cutthroat trout species have been analyzed. Although current conservation efforts and restoration projects have implemented a goal of improving habitat for local species, efforts will be needed to analyze surface water usage with an emphasis on reducing ecological stress. An important next step is to integrate groundwater into the analysis. Well depths and aquifer monitoring could provide a clearer picture of whether declining surface flows are being compounded by reductions in groundwater contributions to baseflow. A dual focus on surface and subsurface systems will be critical to sustaining the Gallatin Valley’s ecological and economic resources under continued development and climate change. In a continually developing region of Montana, management actions will need to prepare for increased stress to surface water use.

Conclusion

The mounting pressure of human development across Montana’s Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, including the Gallatin Valley reveals a complex system of interconnected ecological challenges. From Rocky Mountain elk navigating fragmented migration corridors to native bird species losing critical nesting habitat and westslope cutthroat trout struggling in continuously warming, depleted streams; it is clear there is a human-driven trend reshaping Montana’s ecosystems.

Each of the three focal species examined in this paper provide a distinct dimension of habitat disruption. Elk face physical barriers such as highways, fences, and urban expansion. Native birds receive pressure from the conversion of their habitat to agricultural and urban development. Westslope cutthroat trout endure the compounded effects of water diversion, reduced streamflow, and higher stream temperatures. Together, these three examples demonstrate the destruction and encroachment of three very different habitat compositions.

While current mitigation and restoration efforts are valuable, they are largely symptom focused. Wildlife crossings address the immediate mortality risks for elk, but ignore adjacent habitat lost due to highway driven displacement. Grassland conservation programs protect limited acreage, but cannot reverse decades of land conversion, or reduce urban sprawl. Stream restoration efforts improve local habitat conditions for trout, but do not address water right allocation framework driving the reduction of streamflow. Conservation in Montana as a whole will require a shift to integrated, large scale strategies that address the root causes of habitat degradation. This may include redesigning infrastructure to facilitate migration patterns, nesting areas, and ecosystem health.

The fate of not only elk, native birds, or westslope cutthroat trout, but all species in Montana is not predetermined, but requires action. With coordinated approaches that prioritize habitat connectivity, sustainable land use, and adaptive management, it is possible to maintain the ecological resources of the GYE and the economy of Montana’s growing communities.

Achieving this balance demands the immediate recognition that continued development without ecological considerations will lead to irreversible losses in ecosystem diversity and function.

Anthropogenic and Natural Impacts on Soil and Water Quality in Intermountain West

Ecosystems

Introduction

The Intermountain West is a vast region - ranging from the Sierra Nevadas in the West to the Western reaches of the Great Plains in the East. This region is diverse, containing ecosystems from alpine forests to salt deserts, and everything in between. This region is facing mounting pressures from both anthropogenic activities, and natural processes as climate change intensifies. Climate change has intensified drought conditions and wildfire frequency, and as human activity continues to expand into previously wild landscapes, these ecosystems are facing unprecedented stress. Understanding these impacts is critical for the ecosystems and the communities that depend on them.

Multiple pathways introduce and perpetuate contaminants in the Intermountain West ecosystems. Impacts at the focal point are long-term fire retardants, agricultural herbicides, waterway alterations via damming, and geogenic sources. While these sources all greatly differ in their origins, they all share a common thread: cascading effects through interconnected soil and water systems. The long-term effects of these landscape impacts are amplified by the Intermountain West’s uniquely water limited conditions and biogeochemical characteristics.

The consequences of these extend beyond chemical presence. Soil acidification, microbial disruption, heavy metal accumulation, and altered nutrient cycling greatly shift ecosystem structure and function. Long-term fire retardants introduce large-scale nutrient pulses with cascading effects, herbicides threaten soil biodiversity essential for productivity, dams allow for buildups of contaminants, and naturally occurring uranium and arsenic pose health threats to communities that depend on contained waterways.

Climate change intensifies the pressures of these stressors through increased annual temperatures, reduced snowpack, and prolonged drought. The following review synthesizes current research, identifies necessary further research, and proposes management strategies that contextualize the long-term ecological costs of these short term interventions.

Fire Suppression and Soil Chemistry: Long-Term Fire Retardants in the Intermountain

West By Brodi Maidesil & Noah Heck

Background and Context

Wildfire has been, and always will be, an impactful part of ecosystem processes. Fire has historically served as a cleansing agent. Removing overgrowth from the forest floor, cleaning litter on the prairies of the Great Plains, and serving as a benchmark for ecosystem succession. Fire is a critical component in nutrient cycling throughout ecosystems, and in historically adapted fire ecosystems, many plants have adapted to the impacts of wildfire.

With westward settlement, the practice of prescribed burning saw a decline and was

replaced by a policy of fire exclusion and extreme suppression, which has disrupted

natural fire regimes and interrupted natural ecosystem processes (Fig. 2). A large

factor in the disruption of these fire regimes was the “10 am” rule, instituted by

the U.S. Forest Service in 1935 (Forest History Society, n.d.). This rule was that

all fire starts, natural or human-caused, were to be extinguished by 10am the following

day. In recent decades, management strategies have shifted back towards prescription

burns as an effective management tool, but due to decades of rampant suppression and

fuel accumulations, these natural ecosystems are unable to return to their historic

state without large scale fire events. These disruptions to natural fire cycles provide

context to understanding how modern suppression methods, particularly chemical suppressants,

now influence dynamics at the soil level. This reliance on intensive intervention

has created the need for widespread use of chemical fire retardants. Long-term fire-retardant

applications present

a critical trade-off: while they provide short term and effective suppression that

protect human infrastructure, they also pose long term risks—including soil acidification,

heavy metal accumulations, and microbiome destabilization–that is likely to reduce

ecosystem resilience to future disturbance. With that, it begs the question of “How

do long-term fire retardants impact soil dynamics and biogeochemical processes in

the Intermountain West?”

Wildfire Suppressants

Wildfire Suppressants

Answering this question requires examination of these retardants and their role as

a wildfire management tool. To understand the tradeoffs associated with wildfire suppressants,

it is necessary to examine and understand their context in modern wildfire management.

In wildland firefighting, there are 3 classes of suppressants designated by the U.S.

Forest Service (USFS). The first being long-term retardants (LTFR), commonly referred

to by their brand name “Phos-Chek.” These are the primary suppressants used, as they

are formulated to alter the way fire burns by forming a combustion barrier with cellulose

tissue when those fuels are heated (Adams & Simmons, 1999). They are comprised of

a proprietary blend of fertilizer salts (ammonium polyphosphates), gum thickeners,

iron (for coloration), and water. These retardants are typically concentrated and

diluted with water to ensure uniform dispersal. Due to this, they do not rely on their

water content for effectiveness. They are typically delivered to a site aerially,

and their effectiveness is determined by the volume of retardant per unit of surface

area. In a study on toxicity of long-term retardants and their toxicity to Fathead

Minnows (Pimephales promelas), Phos-Chek D75-R’s toxicity and persistence depended

on the soil substrate it was applied to. It was found that D75-R remained at a toxic

level of 15%-100% after 45 days of weathering, dependent on soil substrate (Little

& Calfee, 2005). It should be noted that toxicity may have changed, as Phos-Chek D75-R

is an earlier formulation used. While formulation has

been slightly altered, current formulations like LC95A and LC95W still retain the

same composition of ammonium polyphosphates.

The next class is foam fire suppressants. These are also known as “short term retardants”, as they rely on their water content to be effective. These primarily contain foaming and wetting agents. The foaming agents impact aerial dispersal, how fast water is lost from the foam, and how effectively it can cling to fuels. The wetting agents determine the suppressant’s ability to penetrate fuels.

The third suppressant type is water enhancers. Enhancers alter the physical characteristics

of water. They change the effectiveness of aerial drops and their adhesion to fuels.

They allow water to cling to non-horizontal and smooth surfaces. Both short term suppressants

and water enhancers are typically delivered manually by ground crews, with applications

on a much smaller scale compared to aerially dropped retardants (U.S. Forest Service,

2019). Given this increasing dependence on retardant applications, it is essential

to thoroughly understand how

large-scale applications interact with soil chemistry and nutrient cycling. These

suppressants have become effective and necessary strategies in managing wildfires

to minimize impacts on human infrastructure and the environment. However, the growing

intensity and frequency of wildfire, in conjunction with human expansion into wildland

areas, has amplified the scale and frequency at which suppressants are used – particularly

in the wildland urban interface, where risks to human health and infrastructure are

highest.

Wildland Urban Interface

This increased reliance on suppressants is directly tied to changes in human interactions

and activities in fire-prone landscapes. Anthropogenic expansion into land that was

once considered wildland has introduced additional conflicts within this new WUI.

The WUI is commonly characterized as the space where urban development interfaces

with both private and public areas defined as wildlands (Davis, 1990). Human development

into these wildland settings has altered natural fire return intervals (FRI), changing

the intervals in which some ecosystems burn, drastically increasing the risk of a

high intensity fire event (Fig 3). Many ecosystems across the West that are accustomed

to short FRI’s, have suddenly seen these intervals become longer, leading to excess

fuel loading and delay of nutrient cycling as nutrients are locked in above ground

detritus (dead and decaying biomass). Literature surrounding detritus pools and their

relation to natural fire is scarce, with virtually no literature regarding the

Intermountain West. Limited research has shown that in an Australian eucalypt forest,

experimental plots that saw a “no burn” treatment exhibited statistically significant

higher Nitrogen and Phosphorus concentrations in litter compared to plots that saw

biennial (2y) and quadrennial (4y) burning. This indicates that nutrients were immobilized

in detritus and microbial biomass rather than cycling back into the soil (Butler et

al. 2020). This pattern of nutrient immobilization in detritus under fire-exclusion

strategies creates a baseline of nutrient limitations, making subsequent mass nutrient

inputs from retardants more ecologically disruptive. Increased fuel abundance due

to changes in FRI’s have compounded with anthropogenic induced climate change as the

West has seen increased average aridity and decreased average precipitation. Those

factors directly contribute to the ease at which fires can start, and the flammability

of fuels in the path of the fire (Fig. 3).

Increases in Fire Occurrence and Severity

Increases in Fire Occurrence and Severity

Altered fire regimes have driven not only a need for increased retardant use, but

changes in fire behavior itself. With such a drastic change in natural fire regimes

in combination with expansion into these wildland habitats, there has been an increased

need for structural protection when fighting wildland fires. In the past four decades,

areas burned by wildfires have nearly quadrupled. On average, 70 million hectares

are burned each year. Additionally, houses in the wildland-urban interface have increased

by 350,000 each year (Burke et al. 2021).

Wildfire-caused structure loss within the American West saw an increase of 246% of

loss per thousand hectares burned between 1999-2009 and 2010-2020. This increase in

structure loss was not correlated to an increase in burned area alone, but from human-caused

ignition, which accounted for 76% of the structure loss (Higuera et al., 2023). This

stark increase in loss was strongly driven by large-scale events affecting communities

that lie within the WUI. These increases in large-scale fire events in recent decades

have necessitated the increased use of aerially applied ammonium polyphosphate based

LTFRs to protect urban structures from wildfire. Between 1987 and 2017, severe wildfires

(characterized as a fire that destroys >95% of trees in burn areas) increased by 800%

(Parks & Abatzoglou, 2020). Correspondingly, from 2009 to 2021, the USFS and other

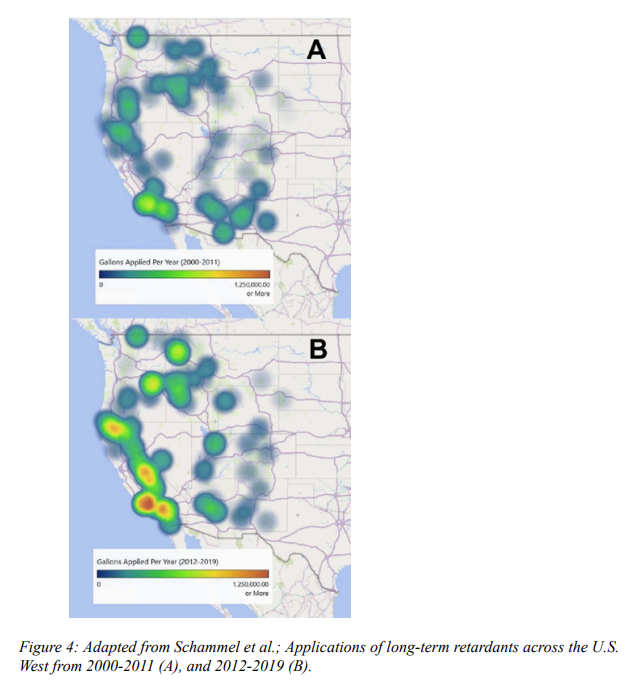

government agencies dropped 440 million gallons of fire retardant on federal, state,

and private land (Tabuchi, 2025; Fig 4). Current fire trends indicate that the West

will continue to see greater fire occurrences and severity, prompting the question

about how

management strategies will follow suit. As long-term retardant use proliferates, it

becomes essential to understand how they interact with soil systems, both the positive

and negative effects, to effectively utilize this tool in a context of long-term ecological

sustainability.

Application Rates

To thoroughly understand the ecological impacts of increased retardant use, it must

be established how much Nitrogen (N) and Phosphorous (P) these applications are delivering

to the soil surface. The formula of the most common LTFR used, Phos-Chek LC95A, is

a proprietary blend and its exact composition is not publicly available. Application

rates per m2 can be roughly approximated using available compositions. The USFS typically

uses a dilution ratio of 5.5:1 of Phos-Chek to water (U.S. Forest Service, 2023).

Perimeter Solutions, the producer of Phos-Chek LC95A, state that undiluted Phos-Chek

has a composition of “80-100%” ammonium polyphosphates, making the final diluted solution

10-15% ammonium polyphosphates (Perimeter Solutions, 2020). The U.S. Air Force is

contracted by the USFS, in which C-130 aircraft may be used as wildfire attack resources.

The C-130 (and similarly sized “large” tankers) can discharge up to 3,000 gallons

of LTFR across an approximate area of 402.3 meters (1/4 mile) long, and 18.3 meters

(60 feet) wide (U.S. Air Force, 2009). Using these numbers and assuming the retardant

is discharged uniformly, it’s calculated that ammonium polyphosphates reach the ground

at a rate of .18 kg m-1

. As Phos-Chek LC95A is a proprietary blend, it’s assumed that the ammonium polyphosphate

fertilizers included is similar to typical agricultural blends, being comprised of

11% N and 37% P by weight. It’s calculated that N is applied at a rate of 176.65 lbs

acre-1, and P at a rate of 594.19 lbs acre-1 (conversion to lbs acre-1 follows standard

agricultural reporting for ease of comparison to agricultural guidelines). In comparison

to agricultural systems within Montana, the recommended P fertilizer (P2O5) addition

to a field of winter wheat.

with a baseline P concentration of 0 ppm is 55 lbs acre-1 (Dinkins & Jones, 2019). Wildland systems are comprised primarily of grassland, shrub, and forested ecosystems that require roughly 1/2 to 1/3 less available P compared to agricultural crops (Plank & Kissel, n.d.). The P application rates from LTFRs per m2 are 10x what would be used in systems that have no available P pool. This represents a nutrient pulse orders of magnitude beyond natural inputs, and even beyond intensive agricultural management. This creates conditions in which plant communities of the Intermountain West have no evolutionary context, creating a higher likelihood plants will experience P toxicity. LTFR dispersal’s high P application rates, in conjunction with its immobile nature, greatly impact microbial communities and the dynamics of these soil systems.

Soil Impacts

Fire retardants induce long-lasting effects on soil chemistry. Ammonium phosphate suppressants introduce large amounts of nitrogen and phosphorus to the soil. Per area, phosphorus inputs from fire retardants are 4 to 44 times greater than farming inputs. While nitrogen inputs are 0.3 to 16 times greater (Moorhead et al. 2025). Specifically, these inputs can cause three-fold increases in labile Nitrogen, 5-fold increases in labile Phosphorus, as well as threefold increases in labile sulphate (Hopmans & Bickford 2003).

These large-scale nutrient pulses rapidly influence the soil system, causing cascading biological and chemical changes. Due to LTFRs being mostly comprised of N and P fertilizer salts, they have the potential to alter soil pH, microbial communities, cation exchange capacity (CEC), immobilization of nutrients in microbial biomass, and shifting competition dynamics among plant species. Microbes are responsible for much of the biological dynamics that occur within soil. LTFR applications introduce large volumes N and P via these fertilizer salts into natural ecosystems. Nitrogen additions via fertilizer salts are linked to soil acidification.

When observing changes to soil pH, the effects of ammonium phosphate retardants vary. One study found an acidification of soil with pH decreasing from 6.5 to 6.0 (Gao & Deluca 2021). In soil with a pH of 5.5, average decreases of 0.3 and 0.2 units occurred. These pH changes were evident 12 months after retardant application. Additionally, ammonium phosphate application immediately increased salinization with a decrease to pre-treatment levels over 12 months (Hopmans & Bickford 2003).

Globally, research indicates that soil pH is responsive to N additions, with an average pH decrease of 0.49. Additionally, temperate forests displayed a greater correlation between pH response and N additions compared to tropical and boreal forests (Tian & Nu, 2015). These findings indicate that precipitation impacts the rate at which N deposition decreases soil pH. While these findings provide a global average, it can be interpreted that similar patterns would be seen within much of the Intermountain West, as the primary ecoregions contained are temperate forests and grassland/scrub landscapes. The Intermountain West in its lower and sub alpine elevations are characterized as “semi-arid,” with higher elevation regions seeing semi-arid characteristics, especially under the influence of climate change.These changes to soil chemistry cause significant alterations to plant and microbial communities.

A study within an Intermountain prairie system on Mt. Jumbo, approximately 1.5 miles

NW of Missoula, MT, was conducted 9 years after LTFR application. The study site was

determined visually through aerial imagery and field sampling, where pink coloration

was present on vegetation and was compared to adjacent control areas. Neither the

control nor the LTFR sites were burned, allowing for identification of LTFRs effects

without fire. LTFR sites

saw an average of 30.6 parts per million (ppm) of available P, compared to 13 ppm

in control sites. There was no significant difference in available N between the 2

sites, indicating that it had dissipated via plant uptake, leaching, and microbial

activity. This study also conducted the same analysis in sites in Bonner, MT, approximately

4.5 miles W of Missoula, MT. This analysis took place 1 year after LTFR application

and saw an available P increase of 6.8x, from 34.8 ppm to 236 ppm. Available N saw

similar trends, increasing 5.7x from 3.98 ppm to 22.7 ppm (Marshall,

et al., 2016). LTFRs present the risk of heightened nutrient persistence on a decadal

scale, having cascading effects. In water limited ecosystems, like the Intermountain

West, this long-term persistence is intertwined with soil pH, microbial composition,

and ecosystem recovery following a large-scale fire event.

Heavy Metal Deposition

Soil acidification and microbial disruptions caused by nutrient loading represents

only a piece of the compounding effects of retardants. Added corrosion-inhibitors,

in the form of heavy metals, introduce an additional layer of contamination that interacts

with pH changes. Soil pH impacts the mobility of heavy metals in soil solution. Typically,

soil acidification increases the mobility of heavy metals through dissolution of the

adsorption of Fe, Mn, and Al hydrous oxides sorbed to soil particles. Protonation

of soil surfaces leads to decreases in CEC and displacement of heavy metal cations

(Cadmium [Cd], Zinc [Zn], and Lead [Pb]) from sorption to clay particles. Limited

studies have shown Cd to become relatively mobile under acidic conditions, followed

by Zn, and Pb in descending order of mobility. Up to 70% of Cadmium’s total concentration

can be extracted (meaning it is free in solution) at neutral pHs from 6.5-7.2 due

to its tendency to be displaced from sorption by Ca2+ and Mg2+

(Kicinska et al., 2022). Due to long-term retardants being dispersed aerially, they

contain heavy metals that act as anti-corrosion agents to protect the flight equipment

that delivers it. One study, focused on Phos-Chek LC-95W,

the primary retardant used by the USFS, contains Chromium at 72,700 μg L -1, Cadmium

at 14,400 μg L-1, and Vanadium at 119,000 μg L-1 after dilution. These metals sit

at 727, 2,880, and 2,380, times the EPA’s limit for drinking water standards, respectively.

They were compared against EPA standards as there is a high likelihood that they will

return to waterways via leaching (Schammel et al., 2024).

Microbial Responses to Fire Retardants

Fire retardants have long lasting impacts on soil properties, leading to downstream

effects on microbial communities. Changes in pH fundamentally restructure microbial

community composition, and impact overall ecosystem function. Soil pH acts as a proxy

for bacterial and eukaryote β-diversity (species richness) in terrestrial systems.

Microbial communities tend to shift towards arbuscular mycorrhizal fungal dominance

as pH decreases (Marshall et al., 2016). Decreased pH lowered the β-diversity for

bacteria, while increasing the β-diversity for

eukaryotes. A large mechanism of ecosystem stabilization that is impacted by decoupling

of these bacteria-eukaryote dynamics, is that of disrupted nutrient cycling (Duan

et al., 2025). This disruption becomes more impactful when considering the changes

in competition between bacteria and fungi. The shift towards fungal dominance and

change in decomposition rates influence an ecosystem's recovery when these effects

are compounded with fire disturbance. The pH-driven effects on soil microbial systems

interact with additional components of fire retardants, particularly heavy metals

and corrosion inhibitors, which introduce further complexity to the dynamics in retardant-treated

areas. Concerning positive feedback loops (a self-reinforcing loop) are created by

increased mobility of heavy metals and the addition of metals contained within these

retardants, which can be amplified by soil acidification.

Beyond responses to soil pH changes and heavy metal introductions, biomass, metabolic activity, and functional diversity reveal the general effect of fire suppressants on microbes. In the short term, one year after application, ammonium phosphate retardants decrease microbial biomass and respiration (Yu et al. 2021, Barreiro et al. 2010). Additionally, enzymatic activity varies with ammonium phosphate fire retardants. In ammonium phosphate treated fires, β-glucosidase and urease activity can be inhibited while stimulated in others (Barreiro et al. 2010). After ten years, reductions in microbial biomass, respiration, and enzyme activity still persist for the same ammonium phosphate treated soils. When compared with untreated burnt soil, these reductions are most prominent in the top two cm of soil (Barreiro et al. 2016). In contrast, others found an increase in functional diversity and metabolic activity with retardant treatment (Velasco et al. 2009). This study monitored changes monthly over a year with seasonal variations occurring due to soil conditions and moisture. Overall, the diversity and metabolic increases were likely stimulated by nitrogen and phosphorus inputs acting as a fertilizer to these soils. The impacts of ammonium phosphate on microbial biomass, functional diversity, and metabolic capabilities can lead to altered nutrient cycling within treated soils.

In addition to measuring changes in microbial biomass, functional diversity and metabolic activity, we can look at specific changes within the community. Five years after a prescribed fire, the abundances of fungi and gram-negative bacteria in burnt soils increased when compared to unburnt soils. Notably, the effect of ammonium phosphate on these soil communities was not significant as bacterial and fungal abundances were similar to untreated burnt soil (Barreiro et al. 2010). Ten years after a prescribed fire, bacteria activity increased while fungal biomass decreased in ammonium phosphate treated soils when compared to burnt soils (Barreiro et al. 2016). This trend contrasts the fungal dominance that occurs with decreases in pH, but can be explained by nutrient spikes that stimulate bacteria, leading to carbon starvation of the fungi. In the short term, fires can have a positive effect on fungal communities, but the addition of ammonium phosphate can exclude fungi in the long term. Going forward, researchers should consider specific changes within fungal communities. Additionally, researchers should consider the impact soil type has on fungal responses. There are many fungi that act as plant symbionts with 90% of terrestrial plants relying on mycorrhiza (Aerts 2003). Looking at specific changes to certain groups like arbuscular mycorrhiza, ectomycorrhiza, and ericoid mycorrhiza can give insights to plant responses to fire retardants.

Beyond community shifts, soil enzyme activity gives insights to microbial metabolic functioning. When looking at specific enzymes, ammonium phosphate treated soils see a reduction in β-glucosidase activity. This reduction is observed both one and ten years after a prescribed fire, indicating a long-term response. This enzyme is responsible for carbohydrate breakdown into sugars. A decrease in this enzyme activity indicates lower rates of overall respiration, demonstrating less metabolic activity. Additionally, ammonium phosphate treated soils see large spikes in urease enzyme activity one year after a fire. This spike in urease activity could have been caused by the fire-retardant inputs. These suppressants usually contain ammonium salts which are similar in structure to urea. After ten years, urease activity slightly decreased, indicating diminished nitrogen inputs in the long term (Barreiro et al. 2010, Barreiro et al. 2016). These changes to enzyme activities can indicate long term changes in soil nutrient cycling.

Plant Responses to Fire Retardants

The effects of fire suppressants on plant communities are better documented. On an

unburned grassland in Montana, ammonium phosphate application resulted in exotic invasion,

as nonnative plants take advantage of nutrient spikes more than native plants. Specifically,

it resulted in cheatgrass (Bromus tectorum) and tumble mustard (Sisymbrium altissimum)

invasion. Cheatgrass is a facultative mycorrhizal plant and tumble mustard is non-mycorrhizal.

These plants pushed out obligate mycorrhizal species (Marshall et al. 2016). Linking

to microbial

responses, ammonium phosphate application results in increased bacterial activity

with decreased fungal biomass in the long term (Barreiro et al 2016, Marshall et al.

2016). Though the invasion was likely caused by nutrient spikes, the impacts on fungal

communities should be considered when observing plant responses to flame retardants.

Looking further into plant responses, the nutrient inputs from fire suppressants cause variable growth of different species. Ten years after a prescribed fire, forested plots treated with ammonium phosphate retardants resulted in larger pine heights and trunk diameters than untreated plots, but the root systems were smaller and more trunk deformities were found in treated plots. Additionally, phosphorus accumulations in ammonium phosphate treated trees were more than twice as high as other treatments. For shrubby vegetation, ammonium phosphate treatments favored resprouter species over obligate seeders. The disadvantage to seeder plants was due to the negative effect ammonium phosphate has on germination and seed viability (Fernandez et al. 2015). Moving to unburned wetland systems, retardant concentrations greater than 12% caused phosphorus values to rise above the maximum level instruments could detect. These nutrient inputs cause significant spikes in algal growth, providing evidence for a eutrophication effect from fire suppressants. Specifically, the algae blocked out sunlight and prevented seed germination of Cattail species, leading to decreased species richness (Rennert and Kneitel 2025). The impacts of these retardants on seed viability and plant community structure should raise concern with current application rates.

Glyphosate in Montana Farming Systems By Anja Bower

Introduction

Glyphosate is another anthropogenic contamination source that affects soil, water, and biodiversity of ecosystems. Glyphosate is a commonly used herbicide across the world and is especially widespread in Montana agricultural systems. This compound is applied to fields of crops to control weeds, reducing resource competition and preventing unwanted plants from being harvested. While farmers benefit from the removal of weeds, the environmental effects of herbicide application prove to be detrimental. The chemicals in glyphosate enter leaves and stems of plants and surrounding soil, impeding growth of crops that farmers are attempting to harvest. Chemicals also enter surrounding waterways, harming aquatic life and contaminating water. Pollinator exposure to herbicides often results in illness or death, and pollinators are essential to the growth of multiple plants and resulting crop yield. The adverse effects of herbicides threaten farms and can lead to reduced crop yields, harming farmers financially and consumers by reducing food availability (Aslam et al., 2023).

Background on Glyphosate

Glyphosate is the active ingredient in Roundup® , a popular brand name herbicide registered

for use in the United States in 1974 by the Environmental Protection Agency. Roundup®

was produced under Monsanto and acquired by Bayer in 2018 (Henderson et al., 2010).

Glyphosate is one of the most commonly used herbicides in agriculture across the world

due to efficiency in removing weeds (Diagboya et al., 2024). Glyphosate is advertised

as relatively harmless, as it biodegrades rapidly in the surrounding ecosystem. Despite

this, chemicals are still released into the environment during the degradation process.

A number of specific fates of this herbicide include absorption, precipitation, and

hydrolysis, all of which carry toxins into natural systems. The main product released

from glyphosate through degradation is aminomethylphosphonic acid (AMPA), which can

inhibit plant growth through

accumulation in the soil or application in high concentrations (Aslam et al., 2023).

Glyphosate targets the shikimic acid pathway in plants, which is an essential pathway

to plant survival. The enzyme 5-enolpyruvylshikimate-3-phosphate (EPSP) synthase is

inhibited, resulting in EPSP deficiency. This reduces amino acid production, which

plants depend on for protein synthesis and resulting growth. Along with suppressing

growth, glyphosate exposure removes green color in plants, causes leaf deformities,

and can kill tissue. Plants usually die completely between 4

and 20 days after tissue death. Mammals do not have the shikimic pathway, and glyphosate

is therefore not as directly harmful to animals as it is to plants (Henderson et al.,

2010).

Glyphosate Effects on Waterways

Glyphosate enters waterways mainly through soil leaching or runoff. Phosphorus is released into the environment when glyphosate degrades, resulting in eutrophication that is detrimental to waterways surrounding farmland. Eutrophication results in algal blooms, whichdeplete water of dissolved oxygen and ultimately kills fish and other aquatic life. This process alters ecosystem structures, with removal of aquatic organisms changing interactions between primary producer species and consumers (Lozana and Pizarro, 2024). Additionally, degradation of glyphosate in waterways releases chemicals, harming processes such as photosynthesis and respiration that aquatic plants rely on for growth. A literature analysis reviewing health effects of glyphosate on organisms in various study locations found that this compound has adverse effects on processes that microorganisms require for survival. Unicellular organisms such as Euglenia gracilis, a type of algae, experienced decreased chlorophyll, photosynthesis, and respiration when a 3x10-3 M concentration of glyphosate was applied. Euglenia gracilis are a primary producer essential to nutrient cycling and provide a food source for other aquatic organisms. When the population size of this algae declines, aquatic invertebrates that consume E. gracilis are faced with fewer food options and could experience malnutrition (Rivas-Garcia et al., 2022). Similar to the food chain disruptions resulting from eutrophication, deaths of primary producers such as E. gracilis alter trophic interactions which are key to ecosystem success.

Glyphosate Resistance in Plants

There are 48 grass and broadleaf weed species across the world that have developed glyphosate resistance, with 17 of these found in the United States (Baek et al., 2021). A study conducted in 2016 analyzed the resistance of Russian thistle to glyphosate on Montana farms. Russian thistle is an invasive plant species that competes with native plants for resources, reducing biodiversity and altering natural ecosystems (Kumar et al., 2017). This study provides an example of the negative effects of glyphosate focused specifically on Montana, and the effect this has at a local scale. Russian thistle significantly reduces the growth of wheat, reducing yields up to 50 percent. Russian thistle is a drought-tolerant plant with early seed production, producing a lot of seeds that can easily and quickly take over an area. The study location was in Choteau County, MT, where farmers follow a wheat summer fallow system. Glyphosate is applied three to four times per year and is heavily relied on by farmers. Thistle takes up a lot of soil moisture, and thereby reduces the benefits of a summer fallow system, which aims to conserve water. Russian thistle was collected from a fallow wheat field, and this specific patch had survived multiple glyphosate applications. Seed dispersal resulting from wind is another method of rapid establishment of Russian thistle in farms, with tumbleweeds frequently forming and dispersing (Kumar et al., 2017). Increasing resistance to herbicides magnifies issues regarding invasive plants taking over dry areas where cereal crop production is abundant.

Effects of Herbicides on Soil Structure

Soil community structure is one of the environmental features most affected by herbicides. Due to soil housing a diverse microbiome with countless ecosystem services, it is also a feature that most greatly affects crop growth and yield. An analysis published in 2023 analyzed the effects of herbicides, fungicides, and insecticides on the abundance and diversity of soil fauna (Beaumelle et al., 2023). This study analyzed 54 different studies focused on the response of soil microorganisms to various groups of pesticides. Diversity was affected even when substances were applied at the rate recommended by manufacturers. The major findings of this analysis determined that herbicides decrease both abundance and diversity of soil microorganism communities. This raises concern at both a local and global scale, with reduction in soil biodiversity creating significant issues for ecosystem health. Microorganisms, which include bacteria, archaea, protozoa, and fungi, break down organic matter and cycle nutrients. The cycled nutrients, including nitrogen and phosphorus, become available to plants and are taken up through root systems (Ortiz and Sansinenea, 2022). Soil organisms compose approximately 25% of biodiversity at a global scale, indicating that their health is critical to the entire environment. (Beaumelle et al., 2023). The depletion of biodiversity results in the need to implement stricter regulations regarding herbicide use and raises questions about potential bans of compositions that are especially toxic.

Pollinator Exposure to Herbicides

Pollinator species experience direct and indirect effects of glyphosate use in crops, often resulting in illness or death of bees. A major indirect effect results from lack of plant diversity, reducing the amount of pollen and nectar available to bees. This also has repercussions for farmers, who rely on bees to pollinate some of their crops and to increase yield. Compounds in glyphosate directly impair the cognitive abilities of bees, disorienting them and making it difficult to find their way back to their hives (Battisti et al., 2021). While many other herbicides contain chemicals significantly more toxic than those found in glyphosate, glyphosate is considered moderately toxic to bees. Direct effects combined with indirect effects of glyphosate exposure are substantial enough to reduce population sizes of bees and create visible effects on crop yield.

Conclusion

Through the analysis of various studies researching the effects of glyphosate in agriculture,

the importance of regulating herbicide application is made clear. Even though glyphosate

is among the less harmful herbicides, the environmental impacts are great enough toalter

ecosystem structure and function. When soil structure is disrupted by chemicals through

the decline of microorganism diversity, plants will experience decreased growth from

reduced nutrient cycling. The animals that rely on plants for food will need to seek

alternative sources.

Ecosystem function depends on healthy soil structure to support diverse plant communities

and the animals that depend on vegetation for nutrition (Ortiz and Sansinenea, 2022).

Other herbicides and pesticides as a whole pose even larger environmental risks, emphasizing

the importance of bringing awareness to the issue and introducing alternative, more

sustainable farming practices.

Dams and Contaminant Toxicity By Taylor Hardegger:

Humans manipulate water systems for their advantages. Dams and reservoirs give us power, recreation and a constant supply of water. We often construct large structures to stop water flow and hold it for the many uses we see fit, but through anthropogenic contamination, invisible risks can hide below the surface. The prevalence of dams and reservoirs in Montana, and across the United States, reflects a balance between the desire to restore degraded ecosystems and the need to maintain sustainable sources of energy and water. While these structures play a crucial role in human activities, they also disrupt natural sediment, nutrient, and contaminant cycles, creating complex biogeochemical environments that can heighten the risk of toxic chemical exposure. Over recent decades, dam construction has steadily declined while removal projects have increased, proving a shift in water management strategies to promote ecosystem restoration (Maavara et al. 2020). In the continuation of this process, we must ask, what invisible harms could present themselves in detrimental ways with the removal of dams in Montana?

Contaminants of concern in Montana originate from both natural and anthropogenic sources.

Potentially toxic elements (PTEs) in freshwater systems that are strongly influenced

by biogeochemical alterations include arsenic and heavy metals. The chemical form,

or speciation, of these elements determines their bioavailability by influencing their

physical state and molecular structure. Additionally, dams physically retain these

toxicants through sediment settling, leading to increased concentration over time.

In doing so, dams not only trap

contaminants but also transform them into more hazardous structures, elevating the

exposure risk for aquatic ecosystems and the communities that depend on these waters

(Maavara et al. 2020).

Dams create ecotoxicological risks by transforming upstream contaminants through altered chemical cycling. Water impoundments such as dams and reservoirs introduce unique biotic and abiotic conditions that change the physical state, and therefore the bioavailability, of PTEs. Elements that more readily enter biological systems, such as those capable of crossing cell membranes or the blood-brain barrier, pose greater health risks. This ability is strongly influenced by their chemical form and physical state. Microbial activity and altered redox dynamics in reservoirs may similarly modify the speciation and bioavailability of PTEs, thereby influencing their toxicity and persistence within aquatic ecosystems. As dams continue to be used for energy production and removed to restore ecosystem connectivity, it is crucial to monitor water quality for the changes invisible to the human eye, an area where current practices and data remain limited.

When it comes to common PTEs, aqueous, clear, and odorless forms are often more toxic

than their solid counterparts. Dissolved particles are more readily consumed and metabolized

than the corresponding solid (National Research Council, 1977). Dammed waterways also

accumulate toxic contaminants in the sediments of still or slow-moving water. While

the total concentration of PTEs remains an important concern, this factor is more

relevant to upstream sources of contamination as they are directly responsible for

the total amount present. Water

impoundment primarily influences the bioavailability and speciation of preexisting

contaminants, thereby modifying their potential risk to ecosystems and human health.

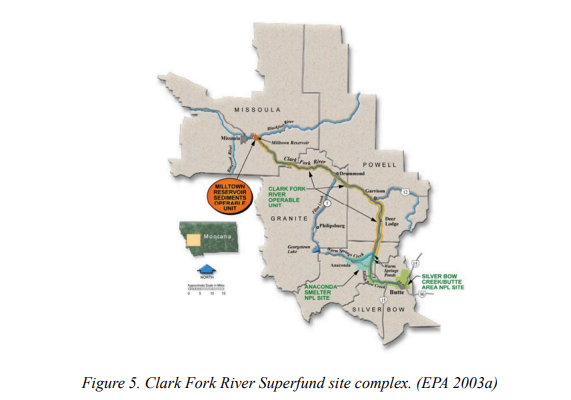

Milltown Dam Case Study